Russian Pilots in Scotland During World War II

Pilots of the Soviet 1st Air Transportation Division in Scotland in 1943-1944

One of the most interesting episodes of the collaboration between our country and the United Kingdom during Second World War is the story of group of Soviet pilots who were stationed in Scotland in 1943-1944. Their task was to receive Albemarle military transport aircrafts and to be trained to fly these planes. The pilots were members of the Soviet Civil Air Fleet’s 1st Air Transportation Division (called Moscow Special Assignment Airgroup, MSAA in 1941-1942, and 10th Guards Air Transportation Division in 1944-1946).

There is now a plaque at the Errol airfield located near the cities of Perth and Dundee that pays the tribute to the Soviet pilots. Commemorative events are held in the honour of the Soviet pilots. However, not much was known about their important mission up until recently. At this page of our website you will find the materials created on the base of researches and publications by Ms Anna Belorusova, a granddaughter of Captain Petr Kolesnikov who was one of the pilots stationed in Scotland.

The Story of the Soviet Pilots Stationed in Scotland

From the very beginning of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 the warfare at the Eastern Front proved to be of unique scale, given the numbers of the troops involved and the vast spaces of the theatres. Given the strategy and tactics of both sides it was also a very mobile warfare. Although the concept of air transportation and mobile warfare was developed in the Soviet Union and suitable planes had been designed and produced well before the World War II, the Soviet High Command experienced dramatic shortage of transport aircrafts that would allow quick deployment of troops at the critical areas of the frontline by Summer 1942. Soviet Government considered number of options for compensating such shortages and following a request from the USSR’s Ambassador to Britain Ivan Maisky in September 1942 the British Government offered to provide 100 Albemarles, two-engine planes that were originally designed as bombers.

Later, on 6 November 1942 Winston Churchill told Ambassador Maisky the background story of this particular aircraft. In 1938 fearing shortage of aluminum, the British Government commissioned a design for a bomber of mixed construction that was later called Albemarle: its fuselage and the center wing had tubular steel frame and wood covering. Once Albemarle mass production was launched, it became obvious that due to complexity of operation the plane didn’t have future as a bomber and would rather be used as a long range military transport aircraft.

Next stage was to choose a route for the transfer of the planes to the Soviet Union. It was decided then to follow the same route that the head of the Soviet Diplomatic Service Vyacheslav Molotov for his non-stop flight to the United Kingdom in October 1942. The planes would depart from Prestwick in Scotland, fly across the North Sea, occupied Norway, neutral Sweden and the Baltic Sea and eventually reach Moscow.

The British Government also offered a training course on Albemarle in Scotland for the Soviet crews. The task to ferry the aircraft was imposed on the Moscow Special Assignment Airgroup pilots.

In accordance with the State Defense Committee Decree of 7 December 1942 ‘On Albemarle aircraft ferrying from Britain to the USSR’ 20 ferrying aircrews were formed in the 1st Air Transport Division. The first group of ten officers was delivered to Scotland on 11th of January by a British Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

The Soviet pilots were accommodated on the RAF Errol aerodrome which was opened on 1 August 1942: three tarmac runways shaped as capital ‘A’ with a two-storied control tower and numerous auxiliary buildings on a wide open flatland. Pilots from a number of Allied countries were undergoing flying training in Errol with around 2 thousand people being stationed there.

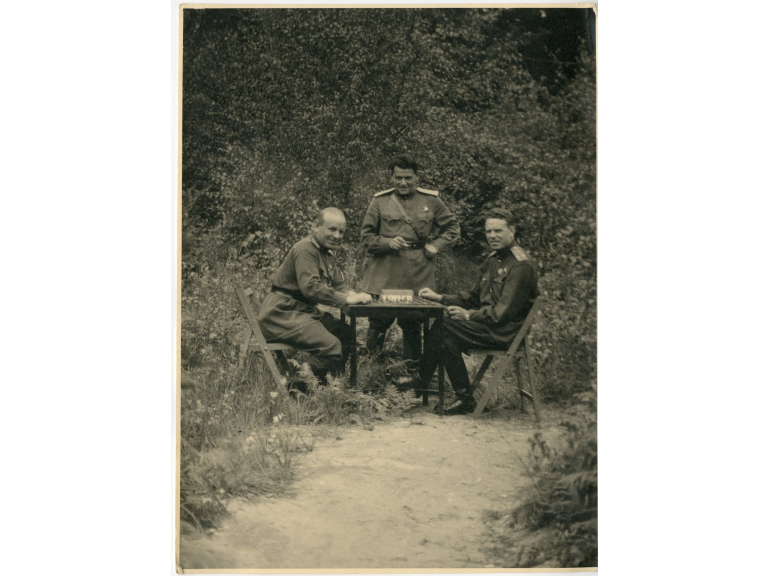

From the report of the Head of the Soviet Military Mission in Britain Admiral Nikolai Kharlamov: ‘Our airmen have started to work on the programme: the pilots and flight engineers are studying the aircraft, engine and equipment at the factories, the radio-operators and navigators are studying equipment in Errol. On 20 January flying training has begun. The air crews are stationed and catered at Errol, conditions are good. A considerable drawback, however, is our airmen’s appearance as they arrived in varying uniforms and without insignia. That complicated communication between them and the British instructor-officers, as the latter consider our pilots to be of low rank.’ Apparently, decision was made after that to order the Soviet Air Forces uniform from a local tailor in Dundee.

In the course of the next two months seven more groups arrived from Moscow. After finishing the training course at the 305th Special Unit at RAF Errol the Soviet crews were supposed to ferry over the first aircraft consignment by the Northern air route by 1 April 1943. In addition to that the British Government expressed its readiness to provide another series of one hundred Albemarles.

Head of the Soviet Civil Aviation Fedor Astakhov reported to the State Defense Committee: ‘The first Albemarle flew from Britain to the USSR on the night of 3 March under command of pilot Shornikov. It took off from Errol airfield on 3 March at 20.45 (Moscow time) and safely landed at Vnukovo airfield on 4 March at 8.00. Flight duration was 11.15 hrs. Altitude was 4-4.5 km. Covered distance was 2662 kilometers.’

By the end of April 1943 the Soviet crews ferried 14 airplanes, two of which failed to reach Vnukovo: one was shot by the anti-aircraft artillery above Sweden, another went missing.

One Albemarle crashed near Loch Tay Lake, during a training flight. There are differing accounts regarding the cause of the tragedy, however, it is certain, according to the eyewitnesses’ evidence, that the crew under the command of the Hero of Soviet Union Alexander Gruzdin was able to lead the falling aircraft away from the houses situated nearby and save the civilians at the cost of own lives.

By the beginning of May 1943 a new challenge emerged. As stated at the report by Mr Fedor Astakhov to the State Defense Committee: ‘There is no enough time for flying over starting from 1 May. The current air route borders with the White nights latitude and our airplanes could be easily detected by the enemy fighters. I believe it is necessary to reconsider the ferrying route with the aim of preserving the flight crews and the planes. I suggest for your consideration the Southern air route for the period of short nights until 1 September, via Algeria – Tripoli – Cairo – Teheran – Baku. Total distance is 10 075km. I request your permission to enter into negotiations with the British to specify the aerodromes of intermediate landings, organisation of technical service and other related issues.’

By June 1943 the air crews training programme at RAF Errol was competed. The Soviet airmen were invited to a tea party with Lord High Commissioner and Duchess of Montrose at the Palace Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh and attended the Scottish Cup Final football game in Glasgow. In spite of top secrecy of the operation, the commanders of the Soviet air crews were invited by RAF Command to the York air station to watch an armada of Halifax bombers take off for a sortie to Berlin.

On 25 June 1943 the British Government confirmed the Southern ferrying route and the Soviet crews went by train to the south of England to RAF Hurn located at the English Channel coast. In July everything was ready for the transfer to Moscow by the Southern air route.

At that time the Red Army Air Force Research Institute presented ‘The Act on Results of the State Test of the Imported Aircraft Albemarle’: although equipped with two powerful Bristol Hercules engines, it had a number of constructive and technological faults. Pilots gave their own assessments: ‘By its flight performance Albemarle does not rank among modern technology innovations... As a Soviet pilot, unfortunately, I am unable to provide a positive review. Commander Yakovlev. Have flown 40 hours and ferried one Albemarle from Britain to the USSR. 20.07.1943.’

On 21 September 1943 a list of the aircrafts faults was provided to the British Government so that such faults could be fixed at the stage of production. The factories were however already under the heavy pressure and couldn’t meet deadlines.

Further transfers of Albemarles to the Soviet Union had to be suspended, as the crews in Errol had to await for the aircrafts to be modified and tested.

This waiting happened to be difficult for the Russian pilots though. The war was raging back home, and their colleagues were fighting the Nazis risking their lives constantly. There also had been no communication with families and friends due to the secret nature of the mission.

One of the pilots wrote in his letter that couldn’t be delivered: ‘Dear Dmitry and Anatoly! My friends! It will soon be nearly a year since I am away from my country and only the first 3-4 months more or less justified this stay, and the rest of the time being like ‘London fog’. No aim, no clear prospects. Back home people are going through the decisive and fierce period or the war and here we are, fifty men in a closed circle feeding our spirit by the daily broadcast reports. I must tell you that the depths of the situation and our moral state can not be conveyed in words. What’s the matter? This is the main question pursuing me as I go off to sleep at 1-2 am and wake up at 7 a.m. in the morning....Your N.... 29 November 1943. Scotland, Errol.’

Finally, three aircrafts arrived by late December 1943, ten more were to arrive soon. By that time, however, another route for another aircraft had already been designed and used: famous Douglas C-47 started arriving by Alaska-Siberia air route, from Fairbanks across the Bering Strait to Krasnoyarsk.

On 14 January 1944 Mr Feodor Astakhov submitted a report to the Soviet Government, where further importing of Albemarle was recognised unreasonable.

In March 1943 the Soviet airmen proceeded in groups to Liverpool, Londonderry, Inverness, Greenock and Thurso. One group boarded a ship that went to the USSR as a part of the Arctic Convoy bound for Murmansk. Other airmen went all the way to Alexandria through the Atlantics, Gibraltar and the Mediterranean with the Royal Navy ships and eventually flew from Cairo to Vnukovo in a Soviet C-47.

On their return to Moscow the airmen were given a couple of days of leave to see their families and then they went back to the frontline. There was one year of war ahead.

Preserving the Memory of Soviet Pilots in Scotland

A tribute to the Soviet pilots who were stationed in Scotland during the World War II was paid in 2015, when the world celebrated the 70th anniversary of the Victory in the World War II. It was made possible thanks to the efforts of enthusiasts from Russia and Scotland, initiative of Captain Petr Kolesnikov’s granddaughter Ms Anna Belorusova, veterans of Russian Civil Aviation and the support from the Consulate General of Russian Federation in Edinburgh.

On 15 May 2015 at the Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre the exhibition dedicated to the Soviet pilots called ‘The Russians in Scotland’ was opened. Speaking at the opening the Consul General of Russian Federation in Edinburgh Andrey Pritsepov said: ‘Their mission stretched far beyond that most atrocious war. Their mission has not ended 70 years ago. By standing united here and now thanks to their children and colleagues in Russia and thanks to the people of Montrose we make sure that it will always stay in our memories making sure that their names and their deeds will be immortal both in Russia and in Britain. We believe that only by keeping memories of horrors and sacrifices of the war we make sure that it will never happen again.’ From the British side the audience was addressed by the Lord Lieutenant of Angus Mrs Georgina Osborne. Delegation from the Vnukovo airport (where the 1st Air Transportation Division was based during the war) and the Scottish veterans were among the most honorable guests.

The exhibition includes the information on the creation of the War-time Alliance between the USSR and the United Kingdom, forming of the anti-Hitler coalition, on the British supplies to the USSR, events happening at the fronts of the Great Patriotic War, and the toughest missions performed by the Soviet air group. Significant part of the exhibition is dedicated to the pilots stationed in Scotland; contributions from private archives were used as well as materials from the Russian Aviation Agency and the Vnukovo Airport museum.

On 16 May 2015 at the Errol airfield that is not in use by the Royal Air Force anymore, the commemorative plaque dedicated to the Soviet pilots of the 1st Air Transportation Division was unveiled. The plaque was delivered from Russia while the base was provided by the Scottish enthusiasts.

The audience was addressed by Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Perth and Kinross Lewis Maitland, Deputy Provost of Perth and Kinross Bob Band, Anna Belorusova, granddaughter of Petr Kolesnikov, one of the Soviet pilots stationed here in 1943, distinguished Russian pilot Aleksey Timofeev and the Consul General of Russia in Edinburgh Andrey Pritsepov. The unveiling was followed by wreath-laying.

The commemorative plaque became another one – and we hope not the last one – memorial in Scotland paying the tribute to those who fought Nazism during the World War II.